The classification of whole wheat, much like corn, is complex. After I started baking my own bread at home, I wanted to try “whole wheat flour” because although I knew it was “healthier” I didn’t really understand why. I also didn’t realize how complicated the world of wheat can be.

“Wheat” refers to many different types of plants and when trying to find the best option for you and your family, all the different types can seem too similar. Wheat is actually a grass and there are about twenty different varieties of wheat including Red wheat, White wheat, Einkorn, Emmer, Durum, and Spelt.

To wrap your head around it, you need a high-level understanding on the different varieties and their pros and cons.

You can organize and understand whole wheat depending on how you want to classify it:

- First, decide how you want to look at wheat. Your options are (1) protein content, (2) how it’s processed, or by (3) variety

- Then, see how I’ve organized wheat under each. this can help you start to get familiar with what type of wheat is best for you

Classification #1: Protein content

Wheat flour can be categorized based on its protein content:

- Whole wheat flour is typically ground from high-protein hard red or hard white wheat, depending on the pigments in the bran layer. These wheats can either be spring wheat, planted in spring and harvested in summer, or winter wheat, planted in fall and harvested in spring. High-protein wheat, particularly spring wheat, is well-suited for making breads

- Whole-wheat pastry flour, derived from lower-protein wheat, also known as soft wheat, is more suitable for pastries

Classification #2: How it’s processed

Another classification of whole wheat is based on its processing method, which is HOW it goes from a whole grain to an end product (such as flour) that you use in your cooking or baking.

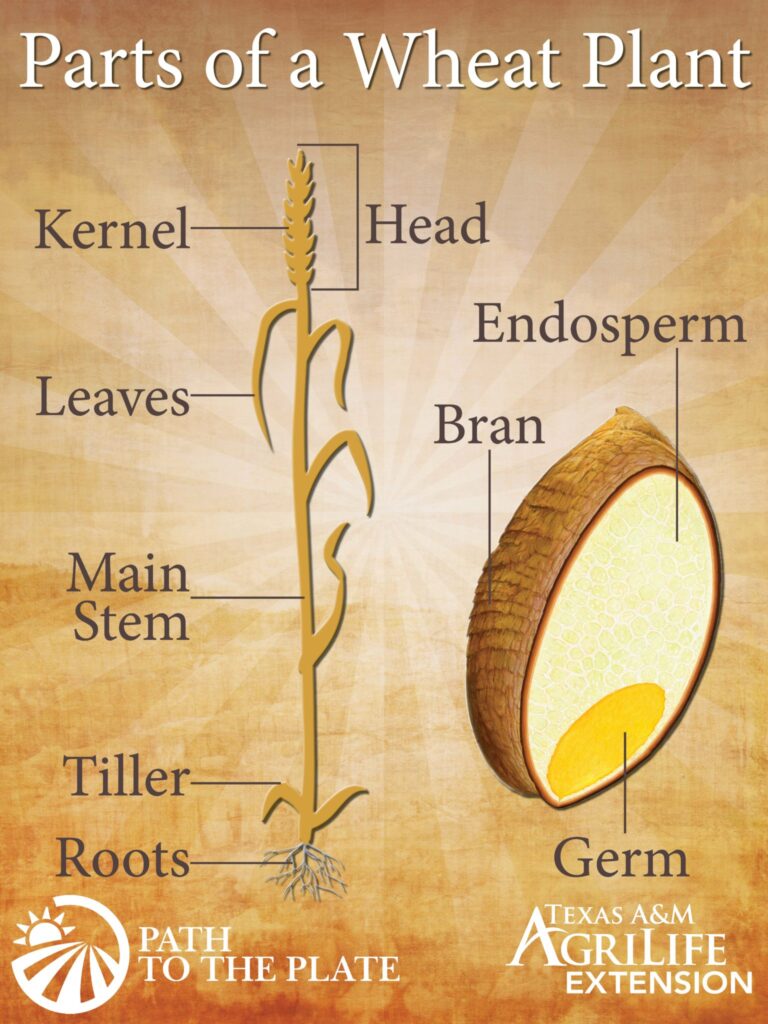

All wheat is “processed” to a certain extent, even wheat berries, as the kernel must be separated from the chaff (both included in the head of the wheat plant) through a process called “threshing.” From there, there are many additional processing steps that can be taken to create different types of wheat products.

These processing methods include:

- Whole wheat flour is ground from a dried wheat berry. Any wheat can be made into a “whole-wheat flour” as it contains all three parts of a a wheat berry: the endosperm, bran, and germ

- White or all-purpose flour is ground flour with the bran and germ removed. Any wheat can be made into “white flour” or “all-purpose” flour

- Graham flour is coarsely ground wheat

- Cracked wheat is wheat that has been chopped, similar to steel-cut oats or rye chops. Think of it as being “cracked” open

- Bulgur wheat refers to steamed, dried, and cracked wheat berries

- Couscous is made from coarsely ground Durum wheat mixed with water, rolled into varying-sized bits, and dried. It’s then rehydrated when ready to eat

- Wheat flakes are pressed very thin from whole berries, similar to rolled oats

- Vital wheat gluten is a processed additive that can be added to low-gluten bread doughs to enhance their rise, with usually one tablespoon per loaf being sufficient

Classification #3: Variety

Finally, wheat can also be categorized by variety, which is how I typically talk about it, as each has its distinct characteristics:

- Durum is an exceptionally hard type of wheat with a high gluten content. When ground into flour, it results in a coarse texture similar to refined semolina. It is often used to create pasta or in combination with other flours to enhance gluten content, allowing for the creation of a more elastic dough

- Ancient wheat varieties, the ancestors of modern wheat, are gaining popularity due to their health benefits, leading to increased availability. Einkorn, Emmer, and Spelt fall into this category, and they are sometimes confused with each other. All three are commonly referred to as “Farro” but I tend to associate Emmer the most with Farro. Although closely related, they do have some differences although they are more nutritious and easier to digest than common wheat. These ancient wheat varieties also possess better disease resistance, making them appealing to farmers who prefer not to use chemical pesticides, and in turn, appealing to conscientious consumers. One reason these ancient varieties fell out of favor over the last century is that they have a hull that is difficult to remove, making their production more expensive.

- Kamut, which is actually a brand name for organically grown Khorasan wheat, is a more recent wheat variety developed by an organic farming family in Montana. It is related to Durum but has a higher protein content. Some people with gluten sensitivity find Kamut’s gluten more tolerable than that of common wheat

- Hard wheat, which is what Kamut and Durum Wheat both are, also includes: (1) Hard red spring wheat, which is planted in the spring and harvested in late summer. It has a higher protein content compared to winter wheat, making it well-suited for making bread and other baked goods that require strong gluten formation; (2) Hard red winter wheat, which is planted in the fall, goes dormant during the winter, and resumes growth in the spring. It is widely grown in the United States and is commonly used for bread-making do to its high protein content and strong gluten; and (3) Hard white wheat, which is similar to hard red winter wheat, but it lacks the bran color genes that give red wheat its darker color. It has a milder flavor and a lighter appearance, making it suitable for baking products with a lighter texture and color, such as white whole wheat bread.

- Soft wheat is commonly used to make whole-wheat pastry flour, which offers a milder taste and texture compared to its hard wheat counterparts